A biography of Clarence Linden Heald as told by his son, Allen Heald, followed by biographical notes about Clarence’s father, Dr. Allen Heald (1829-1907), and his great-great-grandfather, William Heald (1756-1868).

In writing this paper, I am most grateful for the information and advice I have received from my cousin, Alice Heald Sheibley, who is the custodian of our family’s records, and who is recognized as the authority on the history of South English, Iowa, our long-time family home.

(These recollections were read by the writer at a meeting of the Cedar Rapids Literary Club. They were set in type by the author’s son, Theodore White Heald, and printed in Iowa City, Iowa, in 1985.)

Last year Joe Hennessy gave us the lyrical story of Alexander in the County Clare, near the mouth of the Shannon River, — of Alexander who traced pictures in the sands on the Western Irish shore; and we are glad that Joe saved those pictures for us before the inexorable tides of our age washed them away. Joe’s Alexander, as many of us guessed, was Joe’s grandfather; and Joe’s stories tell us much about the land and people and the times of which Alexander was a part, — and help us to know Joe himself better.

I’m doing this with trepidation; but I’ve decided to tell you a story of a different part of the world, a land with different songs and different traditions, with more violent weather, a more rapidly changing culture — and yet in many ways the same. This is the story of my own father; and I feel I would like to tell it here because it is part of the fabric of this American heartland in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s — because it may help you to know me better — and because, frankly, I think it is quite a story, and I want to write it down before it too fades away in those tides that wash Ireland and America and all the rest of our planet.

I’m sure that each of you has their own story of fathers and mothers and grandparents, and times and places, different and yet the same, the origins from which we came together here; and I look forward to hearing a still greater variety of stories from you at our future meetings.

Clarence Linden Heald lived for 90 years. He was born three years after the assassination of President Lincoln; he died during President Eisenhower’s second term. He practiced medicine for more than 60 years. He went around the world in 1897 by ocean liner and tramp steamer; he camped and hunted in the uncharted mountains of Northwest Colorado in 1900. He campaigned among his fellow doctors for one of the first FDA requirements of a warning label on certain medications. He helped the County Attorney in two murder prosecutions. He loved the land; and built waterways and ponds and terraces to save it. He invested his earnings in farms and livestock — lost one farm in the depression, sold and purchased others, and (working with loyal, able farmer-partners) built them into small-scale but efficient operations. In politics, he switched parties more than once; he backed many lost causes; and he savored the anecdotes and the amusing twists of events along the way. The story is perhaps a cross-section of the middle years of our country’s history.

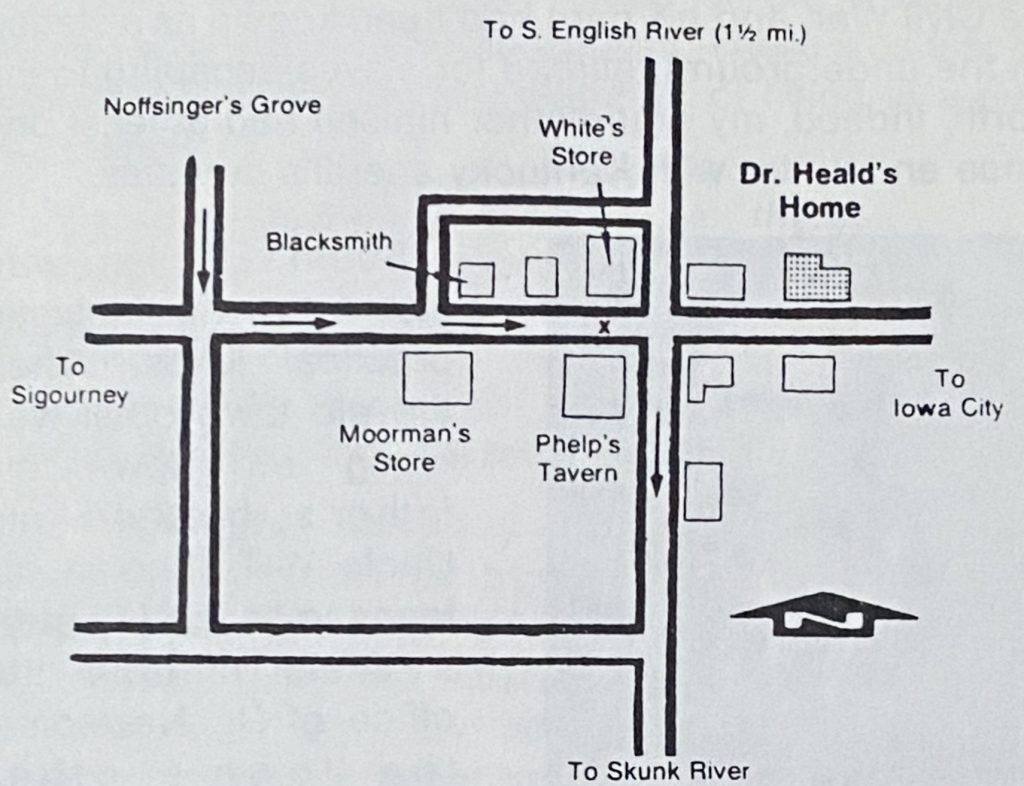

My father was born in 1868 in the town of South English, in the English River Valleys of S.E. Iowa. He was the son of a physician in the town, Dr. Allen Heald, and his wife Rebecca Neill Heald. The name Clarence Linden was borrowed from a character in a novel by Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, that my grandfather was reading at the time.

South English was, and I think always will be, a town of strong loyalties and strong enmities. Five years before my father’s birth, the town was the scene of an incident known as the Talley War, the only bloodshed on Iowa soil during the War Between the States. South English was strongly pro-Union; an eloquent young preacher, George Cyphert Talley, came up from the Skunk River country some 15 miles away — a community settled largely by Tennesseeans — and addressed a pro-Confederate rally in a grove near South English; a crowd gathered in the town; and Talley was shot and killed as his wagon passed through, after the speaking. To this day the story is told in South English.

My grandfather had lived in Southern Indiana before the Civil War, and his barn had been known as a station on the underground railroad for slaves escaping to the North. Indeed, my grandfather himself had at least one tense encounter with Kentucky sheriff’s deputies.

South English was also a town of fantastic practical jokes. When the old town hotel was being torn down, my father’s brother, my Uncle Will, then in his teens, managed to steal a skeleton from the office of Dr. Newsome, the town’s other physician, and hid it in the chimney of the old hotel. My uncle then spread a report that a guest in the hotel had mysteriously disappeared some years before. A crowd gathered; the chimney was dismantled; and the skeleton was duly found. Dr. Newsome recognized the stolen skeleton and shouted “Those are MY bones.” But my uncle quickly caught the doctor’s eye and Dr. Newsome, not wishing to spoil the joke, strode up, took a closer look, and solemnly announced, “No, I was wrong. I never saw those bones before.”

In later life, my father often told of these Rabelaisian escapades; and he often sang the doleful ballads, mimicking the high nasal voices of the wandering singers who came to South English. There was a song presumably about the low standard of living in a rival community:

The potatoes they grow small, over there;

And they eat ’em tops and all, over there.

and there was, of course,

Jesse James was a thief, but was kind to the poor,

And for money he never suffered pain.

At 17 my father was hired as teacher in the one-room school-house in the near-by village of Kinross. The class included small children and boys older and bigger than my father, and the disciplinary problems were unmanageable. My grandfather learned of the situation when he found my father tossing in his bed, unable to sleep; and told him, “Clarence, you don’t have to teach that school any more.” My father never forgot the joy of that release; and I have told the story to my own sons, when they had similar times of desperation.

My father’s sister, my Aunt Allie, did have the knack of managing a classroom and teaching children; and thus she was able to supplement the family’s meagre cash income. Indeed, in her thirties she became the county school superintendent of an adjoining county. With her earnings she made it possible for my father to study medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Concerning my father’s student years in Philadelphia, I remember mainly his stories of oysters on the half-shell, eaten at midnight after an evening’s study — a new experience for an Iowan’s palate in the 1890’s. And there were, always, the songs: a college harmony number “Oh Who Will Wear My Long-tailed Coat?” and a music-hall ballad about Algie, a blackface personality of the time There was one little-known break in my father’s school routine.

He traveled to St. Thomas, Ontario, to be the only witness at the secret marriage of his sister, my Aunt Allie, whom you already know, and my Uncle Chet, whom I now present to you. Both will appear again in this story. For reasons having to do, I believe, with my aunt’s teaching career, their official, formal marriage was postponed until several years later, and the St. Thomas ceremony was known only to my father and, much later, to my cousin and myself.

After graduation, my father served his internship at Scranton, Pennsylvania, and he never forgot one embarrassing experience there. One day he was given the assignment of amputating the leg of a seriously injured patient. He completed the surgery properly, and that evening one of his colleagues suggested that the group go out and “celebrate Heald’s first amputation.” Perhaps because of my Aunt’s unseen protective hand, my father had done little if any drinking; but there were a number of rounds at that tavern in Scranton and when my father at last returned to the hospital, he had difficulty threading his way between the rows of patients’ beds to get to his sleeping quarters. To his humiliation, he realized that some patients were awake, and he heard chuckles of amusement among them. Although he considered this incident a good joke on himself, I believe this early affront to his self-image had something to do with his life-long abstinence from hard liquor.

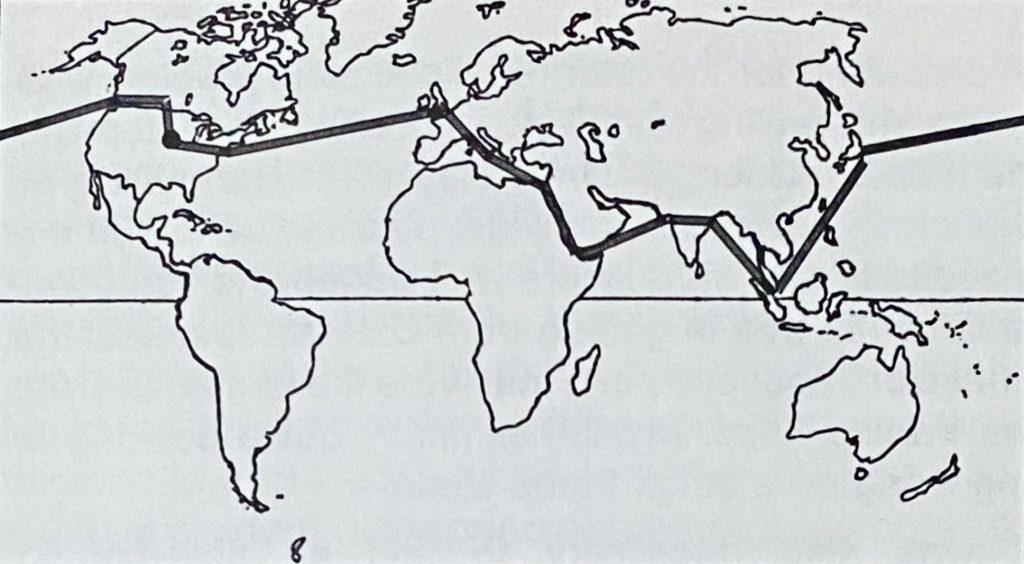

After internship he returned to Iowa and was associated for several years with an established doctor in Ottumwa, some 40 miles from the native village. One day this doctor presented my father with a unique assignment. The son of a well-to-do local family had gone to India with an organization devoted to publishing Bibles and religious tracts; had been injured in a tramcar accident in Calcutta; and had suffered a mental breakdown. The family wanted to send a doctor to bring their son home. The trip involved a round-the-world tour, via Liverpool, London, Paris, Naples, Brindisi, Suez, Aden, Bombay, and Agra, before picking up the patient in Calcutta. Return would include Singapore, the China Sea, Hong Kong, Yokohama, and the Pacific passage.

My father undertook the assignment, and in the spring of 1897 (the year of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee), he embarked on the tour that was to become a legend in our family. I remember countless bits of the story — how in his enthusiasm to see London, he caught the first train out of Liverpool, not taking time to call on Mr. John Morell (to whom he had a letter from an official of the packing plant in Ottumwa); how he toured London by omnibus, and was shown the armor of King Charles I by a guide who supplied a wise commentary: “With all ‘is fine harmor, ‘e couldn’t syve ‘is ‘ead”; how he enjoyed Paris (we have his letter enthusiastically praising the Folies Bergere to the folks back at South English); his visit to the Catacombs in Rome, Mt. Vesuvius and the recently excavated ruins of Pompeii; the slow passage through the Suez Canal in dreadful heat; the little boy who dived for coins in the harbor at Aden; the savage shouts of the workers all through the hot night as they loaded coal onto the ship.

In Bombay, the bubonic plague was raging. My father called on a doctor who took him through an outlying hospital, filled with plague patients. The disease had appeared in Bombay the previous summer, supposedly brought by ship from China, and was just starting to spread to the rest of India. My father understood that he was the first American doctor to look through a microscope at the bacillus of the Bombay epidemic.

Then followed the train trip across India, again in extreme heat, the visit to the Taj Mahal, and, finally, Calcutta. While preparing for the return with his patient, my father stayed at a boarding-house with a small English and American colony; and he quickly fell into the easy life of the western rulers of that country. For the hot nights, there was a great fan, a punkah, suspended from the ceiling and pulled back and forth by a native, a punkah-wallah, at a rope in an adjoining room. If one awoke to find the fan hanging motionless, one shouted “punkah-wallah, tannu” until the man aroused and set to work.

In preparing for the return trip, one main problem was to find a ship sailing from Calcutta that would accept the patient as a passenger. Once they got to Hong Kong or Yokohama, they could easily get passage on one of the big ocean liners, which were well staffed and equipped.

The difficulty was in getting from Calcutta to one of the Chinese or Japanese ports that were the terminals of the trans-Pacific lines. My father finally got a booking to Hong Kong on a small tramp steamer.

It was also necessary to find an able-bodied, reasonably reliable helper for the trip. The job involved a one-way passage to America on short notice; so the candidates tended to be soldiers of fortune, Englishmen who had tried their luck in India and now wanted to look elsewhere. One applicant was rejected when it turned out he had married a native bride, collected the dowry, and was now seeking a quick escape from the country.

Shortly before the embarkation date, my father chose a man, Lawrence by name, who proved to be adequate — although it soon appeared that allowances had to be made. The first afternoon out of Calcutta, Lawrence could not be found. He was not in the stateroom, not on the deck, not in the bar. My father went to the ship’s captain and told him the problem. The captain’s reply was immediate: “Look in the opium den.” Sure enough, the ship had an opium den, and Lawrence was there. I don’t know how serious Lawrence’s addiction was, or what adjustments were required in the daily schedule.

At any rate, when the ship put in for a day or so at Singapore, my father was able to go ashore for some sight-seeing with an English fellow-passenger. They crossed the narrow strait that separates Singapore from the mainland, and found their way to the palace grounds of the capital of the Malay State of Johor. There was an oval race-track, and around the track, a young mar was driving a smart pony-cart at a fast pace. My father and his friend surmised that this was the youthful Sultan of Johor, who had succeeded to the throne of that state several years before. He returned their wave; and after watching his adroit handling of the dashing pony, the two travelers decided to explore the grounds further. No one was on guard at the door of the principal palace building, so they entered, and after going through several chambers, found themselves in what was, unmistakeably, the Sultan’s throne room. Their reaction was inevitable.

Each in turn, my father and his friend ascended the steps and sat briefly on the throne of the Sultan. Then they left the palace and the grounds and returned to the ship. Undetected? Unpunished? We shall never know; but the story does have a brief sequel, if you will stick with me.

In the China Sea voyage, the ship was tossed about by a severe storm. My father always remembered how a passenger turned pale as the ship lurched and sent his deck-chair sliding, stopping just short of the rail.

At Hong Kong the party left the tramp steamer. In his hotel room there, my father could not sleep because a group of Britishers or Scotsmen endlessly sang “Auld Lang Syne”, at an all-night farewell party for one of their number, who was returning home, presumably after a long tour of duty in the Crown Colony.

Aboard the Empress of Japan, after touching at Nagasaki, passing through Japan’s Inland Sea, and making a last stop at Yokohama, the strange expedition headed across the Pacific. The long passage was uneventful. In due course they landed at Vancouver, and took the Canadian Pacific across the Rockies. At Albert Canyon, some distance west of Kicking Horse, the train stopped and the passengers were invited to go out on a small platform to enjoy the view. While my father and Lawrence were contemplating the scene the patient quietly climbed down the embankment and vanished in one of the ravines below. There was nothing to do but secure help; so my father and Lawrence rode the train to the next station, got off with their luggage, and enlisted police help. Marshals, deputy sheriffs, or mounted police — or perhaps all three groups — searched Albert Canyon; found the patient, and the party completed its homeward journey. I do not know how the patient got along thereafter. His family moved to another part of the country, and I believe he was provided with the best specialized care then available. Outwardly at least, his symptoms seem to have involved nothing worse than a desire to play pranks — a syndrome not entirely unknown in the Heald family.

My parents were married in the fall after the fabulous trip, and my father opened his own office in the home village of South English. The practice of medicine in rural Iowa, while not as hazardous as a voyage on a tramp steamer in the China Sea, had its times of fierce encounter with nature — a winter night when my father’s sleigh overturned on the way home from a country call, and my father, clinging to the reins, allowed his horse to drag him home through the snow; and another blizzard when the horse came home alone, and neighbors, alerted by my mother, found the missing doctor trudging homeward. There were times of triumph, as when he devised a small handcar-type cart that he could pedal like a bicycle on the railroad tracks, for calls on patients who lived on farms along the Rock Island branch line that ran through South English.

After several years my father had the first of a series of attacks of tuberculosis. Following the treatment just coming into use, he took periods of rest in Texas, New Mexico and Colorado — after first recruiting another doctor to take over the South English practice. As he grew stronger, he went on a camping and hunting trip by wagon with some Colorado relatives, to the wild country, now popular as a skiing area, around Steamboat Springs. Later he practiced for a time in Colorado Springs, and I recently found a letter in which he told of being engaged by the Antlers Hotel to vaccinate all its employees.

The West, the adventure of the mountains, the chance of acquiring a good ranch or a rich gold strike, lured my father; but I believe he sensed that my mother and her family — as well as Aunt Allie and Uncle Chet — would prefer that he locate near the home town. My father chose Cedar Rapids, some sixty miles from South English. We moved here when I was five years old and he practiced here for about ten years; he built the stucco house at 1939 Bever Avenue; I have the gavel he received as president of the Linn County Medical Society; and I remember his surprise and joy when he was notified of his election as a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons. It should be noted that from the time that the pharmacist John F. Kanealy, Sr. opened his drugstore in Cedar Rapids, my father directed all his prescriptions to the Kanealy firm. While we lived here, my father, in his late 40’s, tried to enlist in the Army Medical Corps for service in World War I, but was rejected because of his history of TB. Indeed, the old tubercular threat did reappear a few years later, requiring yet another sojourn in the West.

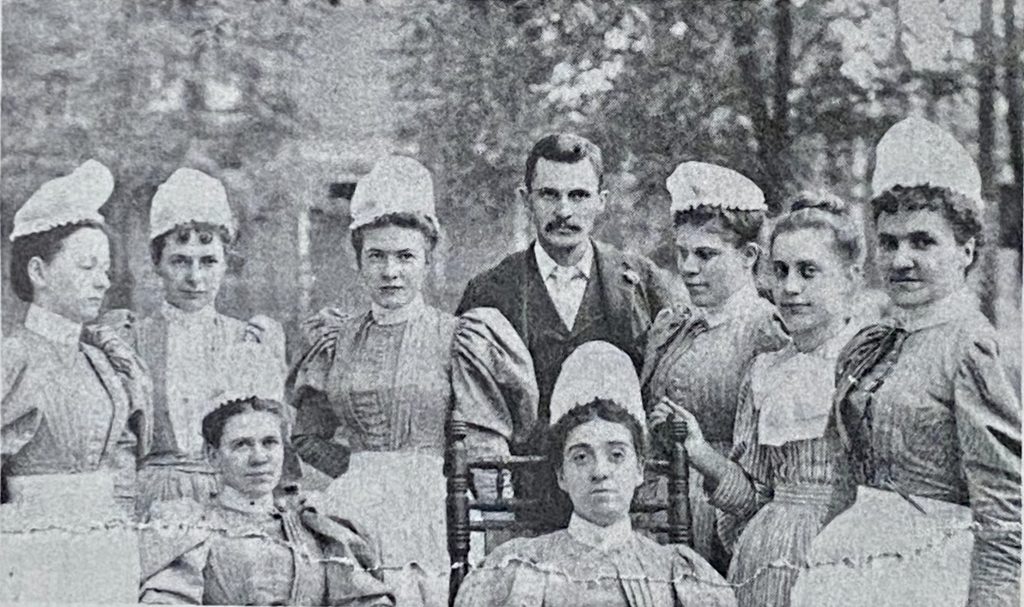

On our return, my Aunt Allie again offered invaluable help. In the county seat town near South English, a substantial building was available. My aunt offered to use her savings to buy this building and rent it to my father for use as a hospital — the only one in the county. The plan offered an excellent opportunity for him to engage in surgical practice with referrals from a wide area, and to be near his family and boyhood friends. He made the move, remodeled the building with ample offices and a large well-lighted operating room and, except for one final Western sojourn, practiced there (usually with an associate) for the remaining 30 years of his active life. My aunt, my uncle, and other relatives and friends spent their last days under my father’s care at the Sigourney Hospital.

Twice during his Sigourney practice, my father found time to take an active part in a local murder prosecution. Feeling that the circumstances strongly pointed to the use of poison, he discussed the evidence at length with the County Attorney, arranged for laboratory work, and testified as an expert witness. One case ended in conviction and a life sentence, the other in acquittal.

Of all his activities, my father was most proud of his campaign for the adoption of a regulation requiring a warning label, to guard against the use of laxatives in cases of stomach pain. Such a pain often is a sign of appendicitis, and a laxative in such cases was likely to cause a ruptured appendix and, frequently, death. In seeking professional support for a warning-label requirement, my father found a strong ally in Dr. Charles Mayo. I recently found a letter that Dr. Mayo wrote to him discussing the adoption of a resolution on the subject by various medical bodies. Despite opposition, the regulation was finally adopted by the Food and Drug Administration. The Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. has given this labeling requirement credit for helping dramatically to reduce mortality in appendicitis cases.

My father was involved all his life in buying farms and improving their productivity. He won several soil conservation awards. My mother’s family — bankers and merchants in the home town — considered him a hopeless plunger. His enthusiasm did lead him, in the boom years of the first World War, to buy a farm that he lost in the recession that followed; and he lost at various times in speculation on the Board of Trade. But in general, his hunches about the land and its potentials proved to be correct. In choosing men for his farm enterprises, he found able, devoted farm operators with whom he formed partnerships and lasting friendships.

My father was a birthright Quaker, a descendant of early settlers in William Penn’s colony. In his student days (believe at my aunt’s insistence) he was enrolled as a member of the Arch Street Meeting in Philadelphia. But since there were no other Quaker families in South English, and no active Quaker meetings in other places where we lived, the family’s church contacts were mostly with other denominations — although my aunt often took part in Quaker conferences and wrote a master’s thesis in Quaker history.

My father accepted the Quaker doctrine of the Inner Light — at any rate he explained it persuasively to me. He heartily agreed with the early Quakers in their protest against liturgy and highly structured church organization. He agreed with the Universalists — mother’s family religion — in rejecting the concept of eternal damnation. And I believe he never forgave John Calvin for the burning of the physician Michael Servetus.

My father always sought a certainty, a specific scientific proof, which he was never able to find in any religious teaching.

During his years in Cedar Rapids my father, along with a number of people with more traditional church ties, became a follower and good friend of Dr. Joseph Fort Newton. He admired Dr. Newton’s eloquence, was moved by his firmness of conviction, and found a kindred spirit in his humor and in his love of Shakespeare.

Like my grandfather, my father read and re-read Shakespeare. Certain snatches of scenes in the plays appealed to him especially, and he would stop to read them aloud to me: the fool trying to amuse King Lear as they wandered in the rain-swept forest, John Falstaff’s humiliation at having to escape concealed in a basket of laundry, and in Macbeth the drunken porter’s long-winded delay in answering the repeated knock at the gate. He often quoted Hamlet’s words,

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamed of in your philosophy.

and I believe that line sums up the hope that my father found in a rich, open-ended universe.

As anti-slavery Quakers, the Healds were ardent Republicans from early times; and so were my Aunt Allie, my Uncle Chet and my Uncle Will; and so was my father, in his younger days. When the Democrat Cleveland was elected President, my father was so angry that he stood in the middle of the main street of South English, shouting sarcasms about the Democrats and Jeff Davis.

According to my father’s own account, he switched to the Democratic side when my Uncle Chet returned to South English from Omaha and told about a speech he had heard there, a speech by the Democrat William Jennings Bryan. Bryan’s speech had not caused my uncle to swerve one inch from his own Republican loyalties; yet my uncle seems to have reported the speech so eloquently that may father was converted on the spot.

My father, I believe, saw in Bryan’s free-silver fiscal panacea an attempt, crude and misinformed but sincere, to solve the economic problems that were causing real trouble for people whom my father knew.

Through the years he ardently supported other leaders and causes that seemed to him to offer hope for ordinary people: Woodrow Wilson; FDR; Henry Wallace: and later Adlai Stevenson. He bitterly denounced men of the Old Guard who blocked the League of Nations, and his anger was intensified by the Teapot Dome revelations which cast doubt on some of the leaders whom my Uncle and Aunt had admired. I remember many bitter arguments around the fireplace on our visits to South English.

What made these arguments particularly vehement and even personal, I believe, was that my aunt blamed my mother and her family for converting my father to the Democratic side. My mother’s family had been Democrats longer than any one could remember. They were, it is true, conservative Democrats; they disapproved of Bryan and disagreed with my father about many of the causes that he supported. But I doubt that my aunt ever realized this distinction. As she saw it, one of the ties that held the family together had been severed, and this, as I now look back on the story, must have been an unspoken factor in the give-and-take around that fireside.

Yet tempers would calm down at last, and the situation would often be relieved by laughter, as my father or some one else in the group was reminded of some anecdote Perhaps my father would tell how Bryan had spoken long ago at a rally near South English, and, as was his custom, had eaten an enormous meal, and suffered severe stomach cramps in the night, and my father was called He quoted the farmer who came to summon him: “Old Bryan’s blowin’ like a stuck steer.”

Or perhaps he told stories about Calvin Coolidge whose quiet humor and lack of pretense my father came to admire.

For my father, as for all of our family, Lincoln was the great national leader of all time — and the great story-teller. I shall include only one of his many Lincoln stories.

Someone had confronted Lincoln with a current rumor to the effect that he was over-fond of the ladies. Lincoln replied that when he was a boy, his mother once accused him of eating the gingerbread that she had made for some special occasion; and the youthful Lincoln replied, “Ma, I reckon there ain’t a boy in Sangamon County that likes gingerbread better than I do, and gets less of it.” I am not sure what context, personal or otherwise, reminded my father of this particular Lincoln story.

When my father was 87, he read a newspaper story that stirred old memories. The Sultan of Johor, that Malay state near Singapore, whose palace grounds my father had once invaded, was celebrating his Diamond Jubilee, the 60th year of his reign. My father wrote a letter to the Sultan, congratulating him and telling him the story of that day long ago, when my father stood by the racetrack on the palace grounds and watched a young man dashing by in a pony-cart. Was that young man the Sultan? Some time later a letter came from the Sultan’s secretary. His Majesty wished to convey his sincere thanks to the doctor for remembering him on this occasion. Yes, the young man in the pony-cart on that day in 1897 was indeed his Majesty.

My father, always eager to keep the game going, this time pushed his luck too far. He wrote to the Sultan’s secretary, rather broadly hinting that he would like to be invited to attend the jubilee.

I don’t know whether my father in either of his letters mentioned the rest of the 1897 story — how he and his friend had entered the throne room and sat, supposedly unobserved, on the Sultan’s throne. Perhaps some one in the court had known, anyway. Perhaps some oriental sixth sense gave a warning. At any rate, my father received, by what must have been return-air-mail, a definitely icy reply from the Sultan’s secretary. His Majesty again thanked him for his interest; but wished to assure him that the Jubilee would be fully covered by the press, and that the doctor could doubtless obtain such information as he might require by reading the American newspapers.

The prophet Muhammad, presumably the Sultan’s ancestor, is supposed to have looked down from Paradise in the year 1571 and seen the approaching war ships of the last Crusader, Don John of Austria, before the naval battle of Lepanto, and said, “That which was our trouble comes again out of the west.” Did that same warning flash across the mind of the Sultan of Johor in 1955, when he realized that this zany American, after almost sixty years, might again threaten the peace of the Sultanate with his shenanigans?

In G.K. Chesterton’s fanciful poem about that battle, Muhammad goes on with his warning against the returning Westerner:

It is he that saith not ‘Kismet’; it is he that knows not Fate;

It is Richard, it is Raymond, it is Godfrey in the gate!

It is he whose loss is laughter when he counts the wager worth,

Put down your feet upon him, that our peace be on the earth.

I guess those words sum up, as well as any, the qualities that would have made my father an unacceptable guest at a Sultan’s Diamond Jubilee.

And yet I think of my father, not so much as a Crusader, nor do I think of him as Cervantes’ foolish knight of the windmills, but as a teller of old stories, a singer of old songs, one who kept alive and conveyed to us some of the feeling of the rich, spacious time of which he was a part — something of the soul of old South English. There is still another line from the same Chesterton poem that perhaps best describes my father as I remember him:

The last and lingering troubadour to whom the bird has sung,

That once went singing southward when all the world was young…

Addenda

For any who might be interested in further details about my father’s life and origins, I am adding the following:

Addendum I: Clarence Heald’s publications and professional activities

Among my father’s papers I found the following, containing details about his publications and professional activities. The information was apparently supplied by him at the request of the publishers of “Biographical Encyclopedia of the World“.

HEALD, CLARENCE LINDEN, Surgeon; born May 20, 1868, South English, Iowa; son of Dr. Allen and Rebecca (Neill) Heald, of Quaker ancestry; educated at Univ. of Pa. Med. School, M.D. 1893; Intern, Lackawanna Hosp., Scranton, Pa.; married Elvina White, Nov. 26, 1896; one son — Allen. Formerly Staff Member, St. Luke’s Methodist and Mercy Hosps., Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Now Surgeon, Sigourney (Iowa) Hosp. Fellow, Amer. College of Surgeons. Member: Keokuk County Med. Soc.; Iowa State Med. Soc.; Amer. Med. Assn. Author: Skin Suture (Surg., Gyn. & Obs., Warbasse & Smythe “Surgical Treatment”), (cited in) standard textbooks on surgical technique; Adhesive Support for Tension Sutures (Jour. A.M.A., Warbasse & Smythe “Surgical Treatment”); A Simple Bloodless Operation for Anorectal Prolapse in Children (Surg., Gyn. & Obs.); Peritoneal Drainage (Surg. Gyn. & Obs.); How Can the Present Mortality From Appendicitis be Lowered (Jour. Iowa State Med. Assn.). This paper was first suggestion of a warning label on laxatives of their danger in appendicitis, resulting in definite lowering of previous mortality. Address: 509 E. Washington St., Sigourney, Iowa.

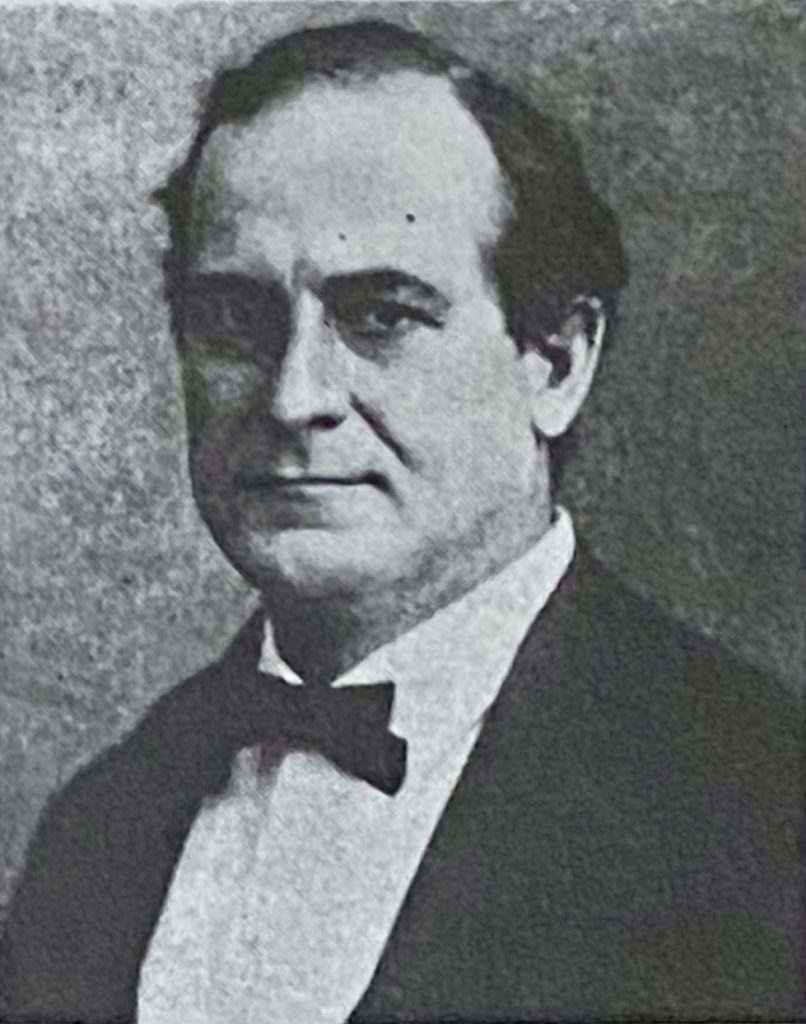

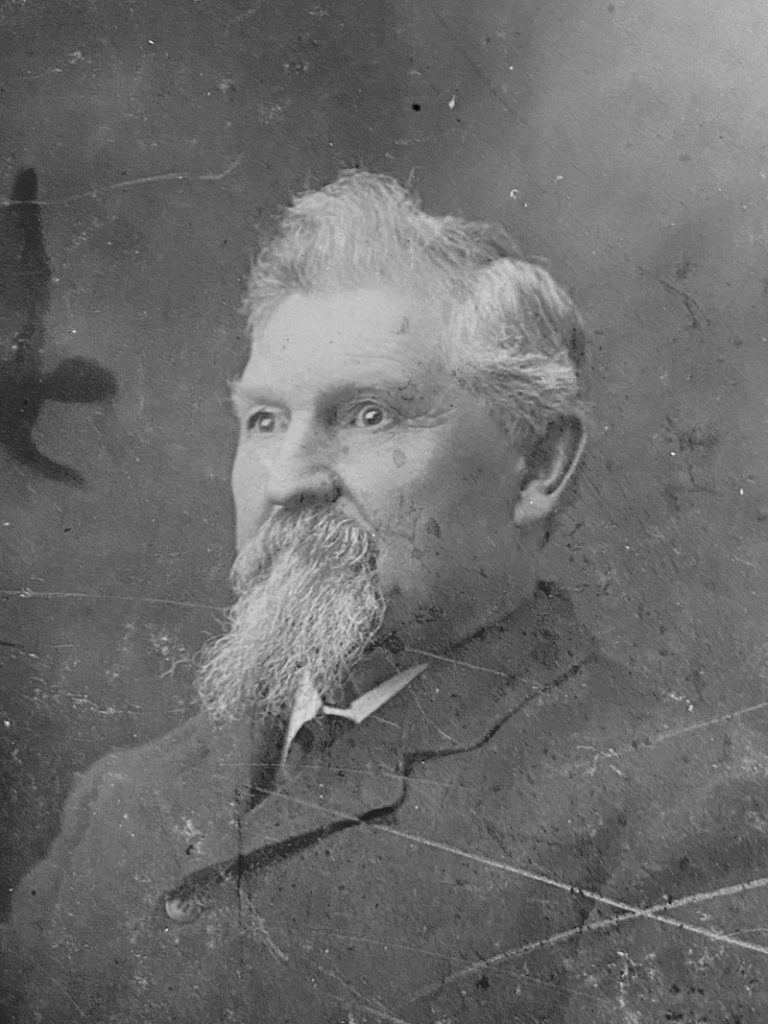

Addendum II: biography of Dr. Allen Heald, 1829-1907

An item about my grandfather, copied from A Genealogical and Biographical History of Keokuk County, Iowa published in 1903 by the Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago and New York. Any one who grew up in rural Iowa during that period will recognize the stilted style and flattering language usually found in the write-ups of “leading citizens” in the series of county histories of which this was one of the latest. The names, dates, etc., are, I think, substantially correct.

“With a long line of prominent ancestors and with a life record of his own that is most commendable, Dr. Allen Heald is well worthy of a place in this work which purposes to give the history of the foremost men of Keokuk county. On the paternal side the earliest record is of the great-great-great-grandfather, whose name was William Heald; he was a native of England. William’s son Samuel came to America with the famous colony of William Penn, thus becoming one of the original founders of the commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The next one in order is Nathan Heald, who was born in Pennsylvania, but afterward moved to Virginia.

Grandfather William Heald was a native of Loudoun county Virginia, and was one of the earliest pioneers of the rich country in Columbiana county, Ohio; he surveyed some of that and other counties; for thirty years he was the government surveyor of that region. He held to the Quaker faith of his forefathers and was one of the prominent men of the country. He was chosen several times to represent the Whig party in the state legislature; he was also able to say that he had cast a vote for the first President of the United States. He lived to the great age of one hundred and two years, and it is recorded that the whole family are noted for their longevity.

Israel Heald, the father of Doctor Heald, was born in Columbiana county, Ohio, and was there reared. His wife was Lydia Allen, a native of the same county and of the Quaker faith; her father, Isaac Allen, was born in Pennsylvania and was an early settler of Columbiana county. In 1868 Mr. Heald came to Iowa and located in Cedar county, where he died in the eighty-second year of his life; throughout his life he was a strict adherent of the religious belief of his fathers.

In Columbiana county, Ohio, on the 1st day of July, 1829, was born Allen Heald; he was the oldest of the two sons by his father’s first marriage, his brother Isaac being a resident of West Liberty, Muscatine county, Iowa. He was educated in a Quaker school of his native county and later in a boarding school at Mount Pleasant, Ohio. Having made up his mind to the study of medicine he began his preparation under Dr. Kay of East Fairfield and remained with him about three years. He studied and was graduated at the Eclectic School of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio. He then went to Dupont, Jefferson county, Indiana, and formed a partnership with Dr. B.F. Richards, his brother-in-law. This was continued for about three years; in 1856 he came to Keokuk county, Iowa, and located in South English, where he engaged in active practice up to 1898, when he retired from the field where he had won such deserved success. He still holds membership in the County Medical Society.

On October 24, 1849, Dr. Allen Heald took as his wife Rebecca Neill, who was born within a few miles of her future husband’s birthplace, the second of eight children born to Samuel and Mary (Cope) Neill; she passed away in April, 1898, leaving three children: Alice is the wife of Chester Mendenhall; William is single and at home; Dr. Clarence L. is one of the leading physicians at South English. Doctor Heald was a Whig and when the Republican party was organized, became one of its loyal members and has ever since cast his vote that way. He has never deserted the Quaker faith of his original American ancestor, and fraternally he was a charter member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows of South English.”

Addendum III: William Heald, 1766-1868

A letter written by my great-great-grandfather, William Heald, a surveyor, on reaching his one-hundredth birthday. (Compiled from two somewhat different published versions.)

1766-1868

Damascus, Ohio, 1st Mo., 10th, 1866.

I was born in Louden county, Virginia, the 10th day of 1st month, 1766, at the foot of a mountain called Short Hill, a spur which puts out of Blue Mountain at Harpers Ferry and runs in a southern direction, which is a gap about 15 miles from Harper’s Ferry, where a small stream and a great road pass through where a village is located on the east side, called the gap, near where I was born.

In the year 1771 my father removed his family over the mountains to a place, now Uniontown, where Henry Beeson was building a mill and had a field cleared, which father got and planted in corn.

The next year he moved eleven miles west, where he had three tracts of land, on one of them he staid two years, when the Indian war broke out.

After he planted his corn he concluded to take his family back over the mountains, and after burying his iron tools and crockery he started, but before he got to where Uniontown now is, where they were building a fort, he broke his wagon and was obliged to leave it and stop at the fort, where we staid all summer. He went back to his farm twice and staid three or four days each time to tend his corn. At one time he took my oldest brother and me with him and while there the Indians attacked the fort.

While we were there the Indians killed a family about three miles from us, on the Monongahela, but the Indians never attacked the fort again.

Two years after this the Revolutionary war commenced, he sold his land and removed to what is called Washington county, Pa., six miles west of Brownsville and lived there in danger of the Indians part of the time.

In the year 1799 he bought forty acres of land with a mill seat on it at the mouth of the Little Beaver, and removed to it. I having been married in the year 1792 removed with him and we built a grist mill and a saw mill.

In the 10th month, 1801, I moved my family to what is now called Columbiana county, Ohio, having sold our mills for $2700. I think in 1803 our county was organized and the first court was held in Mathias Lower’s barn, the jury was not long in the woods.

The court then had to appoint a county surveyor and at that court I was appointed to that office and I was appointed at different times for that office for 27 years.

In the year 1805 l was appointed as surveyor to divide twelve townships into sections and to set quarters, and set corners, so I had to run three lines through each section east and west, and north and south, and set quarter section corners.

My district was in the fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh range joining the Connecticut line.

I began early in the spring and after I performed the work in the woods I had to make three plats, descriptions of each township, one to be sent to Washington, and one for the land office in Steubenville and one for the general surveyor who kept his office in Cincinatti, where I had to go to make out my return.

I was allowed three dollars a mile for my surveying, I had to find hands and diet, my fee came to $1300 and my outlay was $300.

In the year 1840 my wife died. We had nine children. One died when he was 7 years old. All the rest had families. I have had from that time to the present to live with my children. I am now living with my son-in-law, Albert F. Sharpless, and my youngest daughter, Lydia.

When I arrived at my 100th year, all my children living, and a number of their children, and grand-children and two of the fifth generation, assembled with us, when we had a dinner provided for them. Some of them made a calculation, and made out that my children, grandchildren and two of the fifth generation… amount to 160 living.

I voted for Washington when a candidate for President (being 23 years old when he was first elected and voted for him then) and voted at most of the Presidential elections up to the present time.

WILLIAM HEALD

Some further data – and guesses

William the Surveyor died at the age of 102, in 1868, the year my father (his great-grandson) was born.

Sometime during the last two years of his life William appears to have moved from Damascus, Ohio to West Branch, Iowa, where he is buried. The letter contains no hint of any plan for such a move. The 650 mile journey could have been made by train — the Rock Island line had been built as far as Iowa City several years earlier.

It is possible that William’s daughter, Lydia, and her husband, Albert Sharpless, with whom he lived when he wrote the letter, decided to move west, and that William came with them to the Quaker community of West Branch — thus continuing the westward migration that began in 1771 when his father “removed his family over the mountains” from Loudoun County, Virginia.

We know that Albert and Lydia Sharpless completed the trek across the continent, eventually settling in Whittier, California, where my Great-Great-Aunt Lydia was still living, and an ardent advocate of woman suffrage, at 103 (Los Angeles Tribune, 8-22-1913).

A.H.

Greetings. I collect letters that show changing times through individual’s accounts of their lives. Was your Aunt’s name Alice? If so, I have a letter your grandmother in Grinnell Iowa sent to Alice Heald in c. 1889 when Alice was a missionary in Turkey. Happy to share this letter with you if interested.